Following the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump there has been much speculation about the sentiments of the “working class” and if or why they have become aligned to a right-wing politics. It has been argued that the “left behind” industrial heartlands of Britain and the United States have real concerns over immigration, which were being ignored. It has been argued that politicians haven’t catered enough to a racist working class; conversely, the ”working class” has been defended as not racist but sick of being patronised by liberal “identity politics”, “multiculturalism” and “political correctness”. This anxiety over the “working class” is sometimes a projection of liberal racist sentiments which assume the working class to be white. What these uses of the category of the ‘‘working class’’ often evade is the antagonistic history of proletarian composition. And in all cases the working class is never defined through a faithful appraisal of its history.

History shows us that Anglophone working class movements and socialist institutions have in different periods been split along racial lines. There is a long postbellum history of “hate strikes” against black workers who had little choice but to become scabs when sections of US capital used them as strike-breaking labour. The operation of colour bars and segregation and support for institutionalising wage differentials have been enforced by unions, not just states, on either side of the Atlantic. Also in both countries, the sustained popularity of blackface and minstrel shows for over a century points to the desire of white workers (as well as whites of other classes) to accentuate their not-blackness as key to their social and class status. There was support in unions like the Knights of Labour and the American Federation of Labour for the Colonization Movement (i.e sending American-born black people “back-to-Africa”) right up until 1898. A prominent member of the American Socialist Party, Kate Richards O’Hare, wrote a pamphlet in 1912 claiming that a socialist America would deal with the “race question” by putting black people onto reservations, as was already the case with Native Americans. These examples all suggest the deep level to which white supremacy is both institutionalised within workers movement organisations and internalised by “white” workers more generally, over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Respect for history helps us to move beyond many prevailing understandings of race as being about “diversity”, “ethnic minorities” or a multicultural set of interest groups vying for state recognition. Close study makes apparent that white supremacy and colonialism are utterly woven through the development of class compositions. As the late historian Patrick Wolfe put it: “race is colonialism speaking.” Wolfe’s concept of “regimes of race” understands racialisation as a process that unfolds differently depending on specific colonial histories. In what is now the United States, the coloniser tended towards the elimination of indigenous populations through assimilation and dispossession – as what colonisers sought was land. The presence and strength of indigenous people also had a bearing on the prospects for colonisation. The tendency to transport labour to colonies, rather than use native labour – for example African slaves, “Coolies”, indentured servants, or when Britain moved labourers from the Indian subcontinent to East Africa, Fiji, Guyana or Caribbean islands – was partly to counteract indigenous resistance to labour. Whereas the One Drop Rule of racial slavery in the United States was adopted to maintain the labour of those enslaved, and to perpetuate the equation that blackness = enslaved. Different regimes of race have also been impacted by the interaction of productive relations and geographical features such as climate and crops. Theodore W. Allen’s important two-part study The Invention of the White Race, for example, pointed out that the tobacco monoculture pursued by the ruling elite of the Virginia plantation in the early 17th century ate up all the labour-power and left a tiny landowning elite ruling over a vast undifferentiated labouring class. This made social control a perpetual problem for the coloniser as the threat of labouring class resistance also configured the course of this racial regime. The development of racial slavery and of whiteness as a ruling social formation developed as a colonial management solution that can be read back through the archives of Virginia colonial lawmaking, particularly after Bacon’s Rebellion. As Allen famously remarked, alluding to the social construction of race: “when the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, there were no white people.” Whiteness is contingent and has required constant ideological, legislatory and coercive maintenance wherever it has overseen labour and territories. Struggle by those racialised is always a variable factor that can reconfigure specific regimes of race.

What this preliminary excursus into American colonial history is meant to illustrate is that race was integrated for social control purposes in the interests of the colonisers. These historical examples support Wolfe’s formulation of race as “traces of history.” In other words, the variegated processes of colonial settlement and management, and the “race-making” processes that accompanied colonisation show their traces in today’s world as we look at the differentiation of the work of race in a Brazil compared to a United States compared to a UK or an Australia.

Historians of colonialism and racial oppression have in this way illuminated the difficulty in posing a uniform conception of the working class precisely because a national working class is stratified through colonial lines of violence and settlement. Britain is of course central to any account of colonialism and yet there is actually very little discussion – and certainly little proper analysis – of race in the British public sphere. Britain has greatly influenced much of the world in pioneering techniques of colonial settlement and for a long time led the market in the Atlantic slave trade. It has also been a location of numerous postwar and recent riots and uprisings against racist police and institutions, as well as the site of Black Power movements and migrant labour struggles. But anti-racist movements are not even revised as part of a whitewashed history of Britain. These histories are more or less erased and replaced by widely gospel and self-congratulatory myths such as William Wilberforce and the British Government’s abolition of the slave trade out of altruism, rather than economic and competitive advantage and the growing fear of insurrection following revolution in Haiti.

This atmosphere of historical occlusion pertains today even as Theresa May creates a ‘hostile environment’ for migrants and Labour’s Mayor of London plans to ‘significantly increase’ “Stop and Search” policing. This policing technique continues to resemble the infamous “Sus law”, a nineteenth century law against vagrancy repurposed for urban racist policing in the 1970s and targeting black people and people of colour, often children. The recent Windrush cases have suddenly opened up British colonial history to rare scrutiny, forcing many politicians and journalists to scramble for defences or new attack lines. This episode is not however a ‘fiasco’ of state immigration control and while politicians should be held to account, these cases should not be particularised to either sitting governments or those sitting in waiting. It is the contradictory and intertwined development of capital, labour, race and nation in postcolonial Britain that leads to humiliation and violence, sometimes death, for so many people whose lives are dominated by the British border, on a far wider scale than recent Windrush examples. In the following historical account of modern British border controls we ask how it got to this point.

Alien Control

While today we’d be forgiven for thinking that the regulation of people’s movement between countries was a timeless fact of life, the first modern immigration controls in British history actually came in the form of the Aliens Act of 1905. The Act was passed by Balfour’s Conservative government, largely rolled out by the following Liberal government, but much of the force and impetus behind the movement for immigration controls came from the British labour movement. Following more than a century of “free trade” and industrial and trade dominance, the economies of its national competitors were beginning to gain on British capital. Periods of economic downturn contributed to ruling class declinist explanations that blamed foreigners for unemployment, low wages and terrible housing shortages and working class living conditions. As Liberal MP Cathcart Wilson put it, “What is the use of spending thousands of pounds on building beautiful workmen’s dwellings if the places of our own workpeople, the backbone of the country, are to be taken over by the refuse scum of other nations?”

This legislation was the culmination of a long period of cross-class fulminating over the “problem” of Jewish immigrants arriving in Britain after fleeing pogroms in the Eastern European Pale of Settlement in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The content of these “debates” often had “Aliens” as a stand-in for Jews but despite this coded feature, the antisemitism of the discussions was hardly hidden. The context of Jews in Britain wasn’t a new one and pre-modern histories of Judeophobia, such as the longstanding Edict of Expulsion, became attached and adapted to these new waves of migration and the context of further capitalist development.

The well-read socialist publication, The Clarion, said that Jewish immigrants in Britain were: “a poison injected into the national veins.” John Burns of the Independent Labour Party demanded: “England for the English!” Keir Hardie, founder and first leader of the Labour Party and still lionised by most Labour members today, wanted: “Scotland for Scotchmen.” Beatrice Webb, one of the founders of the Fabians, opined that “the love of profit distinct from other forms of money earning” is “the strongest impelling motive of the Jewish race.” She also falsely claimed that Jews “have neither the desire nor the capacity for labour combination,” in order to try to undermine the already significant working class organising among Jewish workers in Britain and suggest that Jews could not be an active or trusted part of the wider working class struggle.

Working class antisemitism in the labour movement, similarly to antisemitism more broadly, developed a two-pronged focus. It railed about Jews taking jobs and undercutting wages but also about Jews requiring state unemployment aid – similar to contradictory tabloid rumour about “asylum seekers” in recent decades. Working class antisemitism at this time also featured early formulations of Jewish world conspiracy that posited a totality of Jewry controlling finance and directing imperialism and other world events. For example, John Ward of the Navvies Union said this in reference to the Boer War at a Trades Union Congress (TUC) conference in 1900:

“Practically £100,000 of the taxpayer’s money has been spent in trying to secure the gold fields of South Africa for cosmopolitan Jews, most of whom had no patriotism and no country.”

Some tried to unify criticism of the rich and poor Jew by saying that working Jews were against integration and organising in unions, and were merely capitalists-in-the-making. Dozens of trades councils and unions all over the country came out in favour of controls. The TUC was itself formally committed to a position against Jewish immigration. Several resolutions in favour of control were passed, including at the Cardiff conference in 1894. The TUC even sent a delegation to meet with the Home Secretary, registering their demand for controls.

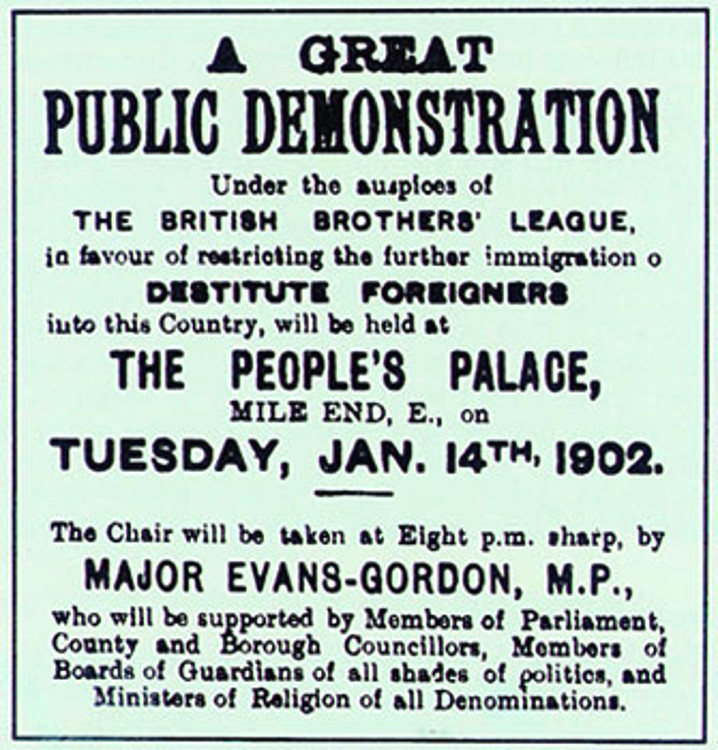

The British Brothers League was a proto-Fascist single-issue campaign in the East End that held rallies and protests advocating for immigration control from 1901-1905. It targeted the area in London where most Jews lived because Jewish immigration was the main focus. The League’s driving force was the Tory MP for Stepney, Major William Evans Gordon, but the pressure group had substantial cross-class and local support. Supporters were known for holding aloft “Britain for the British” banners. These mobilisations prefigured those of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) 30 years later, often marching the same streets and terrifying or being faced down by some of the same Jewish workers. Similarly to the BUF, rallies were heavily self-policed by hundreds of appointed stewards and were attended by many working class people from the area, largely dock labourers and chemical workers.

Poster for British Brothers League anti-immigration demonstration, 1902.

Some working class organisations and publications did take an antiracist or internationalist position – like William Morris’ Socialist League – but practically all consistent resistance to immigration controls was led by working class Jews and Jewish organisations, or Jews having to struggle within existing trade unions against support for controls. The anarchist Yiddish-language newspaper Der Arbeter Fraint (Workers’ Friend), based in the East End, castigated the British working class for their nationalism. The Alien Defence League was set up by Jewish workers during this time, with its headquarters in Brick Lane. A Voice From The Aliens was a pamphlet printed and circulated in 1895 written by a Jewish worker trying to persuade British workers not to support immigration control:

“Surely we cannot blame the foreign working man, who is as much a victim of the industrial system as is the English working man. Neither can we blame the machine which displaces human labour. The only party at fault is the English working class itself, which has the power, but neither the sense nor courage, to make the machines serve and benefit the whole nation, instead of leaving them as a source of profit for one class.”

The pamphlet patiently tries to educate the British working class in some basic aspects of Marxist political economy:

“In Germany the immigration is one-tenth of the emigration. In the United States it is vice versa. Still, the wages of a tailor in Germany is 15s, whilst in the United States it is 58s. What will our opponents say to this?”

“If the English worker has reason to be dissatisfied with his lot, let him not blame his foreign fellow working man; let him rather study the social and labour question—he will then find out where the shoe pinches.”

And, despite writing in 1895, the “Aliens” here are already talking about the need for workers in Europe to find an answer to capital’s outsourcing of production to sites of cheaper labour-power:

“Whether, so far from being the enemies of the English workers, it is not rather the capitalist class (which is constantly engaged in taking trade abroad, in opening factories in China, Japan, and other countries) who is the enemy, and whether it is not rather their duty to combine against the common enemy than fight against us whose interests are identical with theirs.”

Jewish communal institutions – including the centuries-old Board of Deputies, publicly humiliated by radical Jewish group Jewdas earlier this year – were led by wealthier and more integrated Jews descended from earlier migrations in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These Jewish elites were keen to disassociate themselves from newer, poorer Jews. Wanting to protect their own positions and not allow anyone to cast aspersions on their allegiance to the nation, some Jewish MPs such as Harry Samuel, Harry Marks and Sir Benjamin Cohen (made a baronet shortly after his vote) even spoke at British Brothers League rallies and voted for and campaigned in favour of the Aliens Act. Meanwhile, the Jewish Chronicle wavered between pleas for integration and support for restriction and repatriation of Britain’s Ostjuden. Communal leaders and organisations even took it upon themselves to arrange for proletarian Jews to leave for America or go back to Eastern European pogroms. They also sent word to other parts of Europe that no more Jews should come to Britain. This internalisation of British state interests for social control by appointed or self-appointed leaders of varied “communities” is characteristic of a pattern of British race and class management in colonies but also on British soil.

Immigration controls tightened during the First World War with the 1914 Alien Restrictions Act which saw the internment and repatriation of tens of thousands of German and Austrian migrants, as well as more “aliens”. A further 1919 Aliens Act built on the previous two and further restricted the rights of mainly Jews and Germans to settle and work in Britain. Controls remained extremely tight for most of the 1920s and 30s during economic depression, averaging only 700 immigrants per year arriving in Britain. This included the shamefully low number of Jewish refugees admitted who were fleeing from Nazi oppression. Many of those who were allowed to enter were soon deported anyway, and were greeted with widespread antisemitism in the press and from politicians who complained about the few who came.

Whiteness Riots

“Race riots”, essentially anti-black and brown pogroms, and lynchings are horrifyingly commonplace in US history but have also happened in Britain, such as the wave of attacks in major British port cities in 1919. We’ll expand on this because it’s an interesting case study in the history of both popular and state racism on British soil.

In the last years of the nineteenth century and the early years of the twentieth – though there have been people with black and brown skin living in Britain for centuries – British shipping companies hired more black and brown workers as seamen, needed to help circulate commodities to and from Britain and around the Empire and the world market. This meant that men, mostly from East and West Africa, the Caribbean, the Arabian peninsula, Somalia or Lascars from the Indian subcontinent, would be picked up at ports around the world, usually taken on at lower wages than their white counterparts, and would finish up in British ports like Liverpool, Cardiff, London, Bristol, Hull, Glasgow, Newport, South Shields and elsewhere. All apart from Bristol would see racist rioting and violence over the course of 1919.

These men would then find themselves having to wait for more work on other ships to come along, settling in said British port towns in the meantime, encountering constant state and popular racism. Almost entirely colour-barred from all other work and discriminated against in housing, most men found themselves in hostels, living off charity or whatever government assistance they could access. Many were homeless and starving – conditions which also helped British shipping capital to harden the racial division of labour.

During the First World War, as white shipping workers were drafted to serve at the front, there was greater demand for colonial labour in the shipping industry and wages began to rise. Some black and brown seamen began to prosper – relative to the prewar period, though most still lived in slums. Black home ownership began to rise in this period and some workers were able to build up some savings. Some black and brown seamen began to set up home with and even married white British women. At the end of the war, as white servicemen demobilised and returned home to an economic downturn and growing unemployment, shipping bosses explicitly began to replace black workers with white under pressure of (white) nationalist fervour, including from trade unions and Labour Party politicians. The TUC passed a resolution condemning “Asiatic Labour” and demanded preference for white British workers before any others. Chinese immigrants had previously been targeted for attacks in Cardiff in 1911, and were later targeted for deportations. At the time, workers from the Seamen’s Union refused to work on any ship which employed Chinese seamen, even arguing for the rights of “Coloured British” over Chinese.

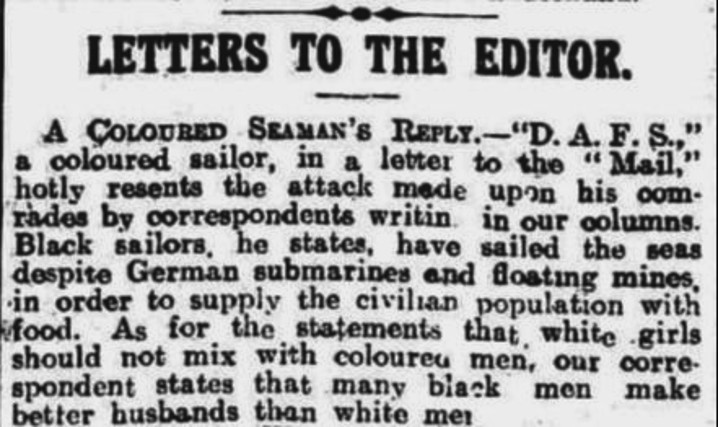

As well as complaining about “colonial labour” undercutting wages, unions and white workers also made racialised moral arguments about the undesirability of black people’s presence in Britain, of their inherent immorality and their being a drain on taxpayers for claiming unemployment relief. Media coverage amplified such feelings and moral panics about the safety of white women, the resentment towards supposed black prosperity or social equality and the threat of miscegenation proliferated. This provided the context for the racial violence that erupted in port towns across the country in 1919.

While disturbances happened elsewhere we will limit ourselves to a brief focus on events in Liverpool and in Wales. In Cardiff, as in other Welsh ports, there were beatings, gunfights and stabbings. Black people’s properties were attacked, as were Greek and Chinese-owned businesses. The Cardiff Argus newspaper reported a particularly horrifying incident in Glamorgan where a West Indian man’s funeral was attacked by white locals. The coffin was broken open, the corpse’s head was severed and the attackers played football with it, before police intervened. Such racial animus from whites – a visceral, bodily hatred that operates beyond or far in excess of any supposedly delimited or “rational” economic grievance – has been a consistent hallmark of European colonialism.

In Liverpool, a black man named Charles Wootton appealed to a policeman for protection amidst the riots but the police stood by as Wootton was pushed into the Mersey river. Onlookers cheered and threw objects until Wootton had drowned. These anti-black pogroms in many of the towns carried on for several days, often until police reinforcements and soldiers were drafted in to restore the kind of “order” that set the conditions for this all in the first place. Scores of arrests were made, a majority of those arrested in many towns were black.

The aftermath saw counter-riots and outcry in some African countries and parts of India. In Britain, the authorities decided they needed to act. With the 1925 Coloured Alien Seamen’s Order the British state attacked the right of work and abode of non-British seamen based on skin colour. The de facto effect of the legislation was to make life harder for all black and brown seamen regardless of whether they were British subjects and had just fought for Britain in the war. It was made much harder for people of colour to work and settle in Britain through complex identification regulations and the racism of those enforcing them. As many of the men were never issued passports in their home countries they were constantly harassed by police and denied work upon arrival in Britain. This wasn’t the first and wouldn’t be the last time that British nationalism blurred the lines between race and nationality. British shipping began to fall behind, higher and longer unemployment became the norm and black seamen suffered the most. Many were repatriated or chose to leave themselves. Many others struggled and stayed, and several people in Britain today can trace their descendants back to them.

Such examples are not solely about the manipulation or “divide-and-rule” work of race but also point to the longue durée history of “white” proletarians (a malleable and changing category) actively choosing to identify with whiteness, or not-blackness, underlining how historically one-way calls for “unity” or “black and white: unite and fight!” have been.

“A Coloured Seaman’s Reply”, published in Hull Daily Mail, March 1919.

Work (but don’t stay)

After the Second World War, Britain was a country rapidly withdrawing from its colonies, damaged by bombing, indebted to a new superpower and struggling with labour shortages. In this period it returned to something of an open border regime. A notable exception to this was the hasty and violent repatriation of Chinese seamen from Liverpool, but there was otherwise a large influx of European refugees and displaced persons. Unlike many other European countries, Britain also had access to a ready labour-supply in the form of its colonies that it had purposely underdeveloped and exploited for centuries. British Commonwealth subjects from the Caribbean, the Indian Subcontinent and West Africa began to arrive in growing numbers as cheap labour-power to work in Britain’s industries, drive its buses and staff its new National Health Service. At first, a majority of those who came were men, like the seamen at the beginning of the century. This was aiming to be a kind of gastarbeiter system, whereby “colonial labour”, expected to be single and only stay temporarily, represented low reproduction costs for British state and capital as black and brown workers faced super-exploitation in the workplace, from slum landlords and pervasive racial discrimination and ghettoisation. Super-exploited migrant labour was one of the building blocks of the sustained economic growth and near-full employment of the much-celebrated postwar period.

The period that anticipated new immigration controls saw riots against black communities in Notting Hill and Nottingham in 1958 and the targeting of “coloured” neighbourhoods by Teddy Boys. The immediate postwar period saw Oswald Mosley’s attempt to rebrand his fascist movement as the Union Movement but was fought off again by militant working class Jews. He left Britain for some years but returned to try to take advantage of the Notting Hill riots by standing for election on a platform of repatriation of Caribbean residents and proposing laws against interracial marriage. Other new fascist groupings like the original British National Party and Colin Jordan’s split from it, the National Socialist Movement, emerged in the early 1960s and agitated for immigration controls. Also influential in this campaign were racist pressure groups like the Racial Preservation Society and the Birmingham Immigration Control Association who lobbied mainstream parties and politicians at the local level, resembling earlier incarnations like the British Brothers League who pushed for Alien Control. These were all manifestations of the building racism and white resentment towards black and Asian migrants. As more families made the journey over, more black and Asian women began to work in the factories and public services and their children attended schools. Black and Asian communities, most of whom initially imagined they would return home at some point, became more militant in defending themselves and more determined that they were not visitors but “settlers”, particularly the next generation who were born in Britain. The British state began to consider its options. The cheap labour needs of capital and the social control mechanisms of the state were in growing contradiction. The ruling class, as well as many working class whites, increasingly agreed that black and brown immigration was the problem.

The Tory government’s solution was the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962, ending automatic right of entry and settlement in Britain for Commonwealth subjects and setting up an instrumental system of employment vouchers that quickly did away with any unskilled immigration. Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell held steady against controls though his position was largely based on a kind of colonial sentimentality about “Mother Country” duties. The common argument of the Labour Party was that “the economy”, framed benignly as a mutually beneficial national abstract, should determine how many immigrants would come and go. As we shall see later, this position is similar to Labour’s manifesto today. Harold Wilson, who became leader after Gaitskell’s death, embraced controls more wholeheartedly when in government, further restricting “coloured” immigration with a white paper in 1965. Jim Callaghan, later to be Labour Prime Minister, is quoted by Tony Benn as saying in 1970, two years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech: “We don’t want any more blacks in Britain.” Rather than British capital absorbing the agricultural labour made surplus by industrialisation and urbanisation in its (post)colonies, it became the brain-draining cherry-picker of the most skilled workers. The TUC supported Labour Party policy on immigration control throughout this period.

The 1962 act delinked immigration policy from economic determinants, and became a more directly political state intervention attempting to draw a line under “coloured” migration and settlement by setting targeted restrictions on “Commonwealth” immigrants. These were restrictions that tended not to apply to whites from Canada, Australia, South Africa, Rhodesia and New Zealand who were considered “patrials” under Labour’s 1968 Commonwealth Immigrants Act, as they could trace their family lineage back to British soil. In reality the legislation was rushed through because Wilson’s Labour government were terrified that Britain would have to accept all of the Kenyan Asians being made stateless by Kenya’s “Africanisation” policy. Further acts under the Conservatives in 1971 and 1981, as well as Britain’s 1972 accession to what would become the EU, cemented racist British immigration policy as a consensus across every government since. Only pre-1971 non-white Commonwealth subjects gained status and citizenship, after that the processing of Commonwealth subjects to work and settle and eventually gain citizenship was shown no favouritism, and was subject to their economic contribution and “good behaviour”. There was increased scrutiny on suspected “sham” visa marriages, particularly on women arriving from South Asia, as British authorities under Labour and Tory governments conducted “virginity tests” at UK airports and High Commissions. This series of legislation over two decades cemented racism at the heart of British law on immigration, nationality and citizenship. As we’ve seen in recent months, even pre-1971 arrivals aren’t safe from today’s hostile environment.

Asian Workers Struggles

In the 1960s and 70s Asian workers in Britain largely found work in factories and workshops in the Midlands, the North West and parts of London such as Southall and Brent. These were the kind of industries where profits were gleaned through absolute surplus value (i.e. extending the length of the working day), not relative surplus value (i.e. through productivity improvements via automation or improvements to the organisation of work). Workers were low paid, worked long hours, in dangerous and unhealthy conditions. Intensity was driven up and overtime was constant as these were the primary means for firms to return a profit. All in all, these were positions that white British workers were beginning to be able to leave, turn down or oversee (for a higher wage) as a racial division of labour prevailed.

Many strikes and workplace struggles by Asian workers were over union recognition, colour-bars that prevented Asian workers from getting promotions and racist insults from superiors or co-workers that ranged from the overt to the subtle. Another key antagonism was the role of “charge-hands” – white English overseers who extracted bribes in exchange for hiring workers and giving out overtime.

The Race Today collective wrote of the 1974 Imperial Typewriters strike in Leicester:

“The divide between the organised white labour movement and the organised independent struggle of an Asian workforce became a historical fact, one from which there was no return. The strike lasted three months. What was the strike about? It was an organised assault on the colonial relations that characterised the employment of Asians in Britain. The workers, who walked out of the factory on May Day 1974, complained about the low pay, the fiddling of bonuses, the constant harassment of the workforce for more productivity, the imbalance in the production targets given to blacks and whites, the non-existence of Asian shop stewards, the restrictions that made up their daily working lives as compared to those of the white workers – washing time, tea breaks, lunch breaks, toilet breaks, dignity.”

Important in many of these struggles in the 1960s and 70s is the role played by union leaders and shop stewards (almost entirely white). Again and again, what emerges is that their primary aim was to control and manage struggles by racialised workers, prioritising the corporatist compact of negotiation between representatives of labour and capital, while showing little interest in the fact that the category of labour was tiered through racism and at the behest of race privileges. This necessitated the autonomisation of struggles against racism and super-exploitation that saw Black and Asian workers come up against bosses, politicians and police, but also unions and white workers. Unions, such as the Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) in the case of the 500 Asian workers who went on strike at Imperial Typewriters, continually showed no support for strikes by Asian workers. By way of an excuse they would regularly reference the workers’ failure to follow procedure. George Bromley of the TGWU said of the Imperial strikers, “[they] have got to learn to fit in with our ways.”

In the absence of worker solidarity, communities of colour were often able to rely on support and solidarity from migrant communities, from petit bourgeois shopkeepers to fellow workers, with women doing much of the invisible caring and reproductive work as has always been the case in strikes. What complicates this picture is that the militancy alone of such strikes probably wouldn’t have received union-backing even if the strikers were white because the radical actions went against the political positions taken by union leaderships and the bargains they had made with government. In short, there was a combination of reasons why white workers and white unions were not demonstrating solidarity with Asian workers. Racism was not the only reason, the other was that unions as a rule were not supportive of militancy, especially when coming from outside of the organisation.

The ultimate example of community solidarity was the seminal Grunwick strike in North London. Led mostly by East African Asian women it was only defeated after nearly two years, largely due to betrayal by union leaders. But as well as receiving huge support from the local community it also garnered more widespread support than any other industrial dispute by racialised workers in British history. This included rank and file postal workers refusing to deliver for the Grunwick company, some more “official” support (though unions were always more likely to support struggles that were largely fights for union recognition) and huge turnouts at mass pickets from students and radicals, despite facing extreme violence from the police. Although the strike was eventually defeated, the intensity of the struggle marked something of a change within the workers movement. Of course it’s important not to be starry-eyed about how much this strike changed. Support for super-exploited migrant workers from mainstream unions remained and remains inconsistent and patchy, often worse than that. And at least part of the reason why migrant workers from the colonies (and their children) eventually began to be integrated into mainstream British unions was because of the success and militancy of their autonomous workplace struggles during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – some of which stemmed from carrying forward the personal experience or collective memory of struggles in the Caribbean or the Subcontinent.

Securing the borders, when the border is everywhere

Throughout the period of Thatcher, New Labour and post-2010 Tory rule, the British state has been tightening its grip on the function of the border and ratcheting up the punitive assemblage of security, welfare/workfare, immigration and imprisonment to stratify and discipline the working class in Britain. This process has seen the further securitisation of society, particularly after 9/11, and the demonisation of “Muslims”, “illegal immigrants” and “bogus asylum seekers” by politicians, the press and many others in society. These terms appear in scare quotes because the process of this demonisation makes each category a racialised figure and so helps to widen out the ascription beyond people who directly fit each formal description. Both parties and the reactionary political climate have constructed a system where people seeking asylum in Britain, hoping to gain refugee status, are not allowed to work in the meantime and are forced to live off meagre government vouchers, and cash payments of as little as £29 a week.

Britain’s border regime includes huge numbers of deportations, including by mass deportation charter flights. There has also been a steady cross-party expansion of detention, criminalisation and imprisonment of immigrants, as well as the invisibilised racist state violence of “no recourse to public funds”. The ‘hostile environment’ policies set out in the Immigration Act of 2014 casts a social and technological dragnet across every area of civil society. It aims to enlist the citizen-worker in the national duty of capturing fugitive “illegals” by making a border guard out of every teacher, doctor, landlord, bank employee and data analyst. Since as early as 1996, immigration legislation has involved employers playing a similar role.

Of course, the exteriority of this process is the contribution a country like Britain makes to the movement of peoples across the world. By making endless war (and refugees), contributing disproportionately to climate change and benefitting from the imperialist flows of capital, trade and value-extraction it is inevitable that some labour follows capital to the metropole. And in so doing it encounters the walls and waters of racist murder that make up Fortress Europe. The EU and its member states have increased the militarisation of border zones, criminalised solidarity and invested in the security infrastructure of deportation zones. Ultimately, the EU is now geographically holding off and juridically invisibilising migrants by, for example, outsourcing its border control to Morocco, Turkey, and Libya, even as early as 2010 when Muammar Gadaffi promised to help stop Europe from “turning black”. Meanwhile, Britain builds mega prisons in Jamaica and Nigeria so that it can “send home” nationals from those countries incarcerated in British prisons.

Corbyn’s Labour and the immigration question

The question of immigration lay at the heart of the Brexit referendum and continues to be a primary point of conflict within the Labour Party and trade unions, and among Corbyn supporters and the wider left. As we’ve seen, nativism and racial exclusion, as well as a structural embeddedness within imperialism, has long characterised the British trade union movement and Labour Party policy. Prominent figures on parts of the Labour left have been clearly messaging about the need for a much anticipated Labour government to “do something” about immigration. This messaging is constantly framing immigration as the problem affecting wages and living standards. Len McCluskey, general secretary of the Unite union, said recently:

“workers have always done best when the labour supply is controlled and communities are stable. While we must reject any form of racism, and help refugees fleeing war, we must also listen to the concerns of working people.”

Here the regulation of the labour supply is held up as a solution for ‘working people’ and communities. This is not just an unfortunate use of words. This statement betrays a form of social imperialism deep-rooted in the British labour movement. The more specifically structural and contemporary reasons for union leaders to take up such positions is neatly summarised here by Bue Rubner:

“In the face of surplus population, trade unions will have their bargaining power undermined by the increasing competition from the un- or underemployed, and some will engage in a losing battle to lower competition through enhancing the exclusion of some groups, on grounds of race, gender, or citizenship status.”

In a recent essay for Novara Media, Paul Mason used the electoral rise of the far right in Germany and Italy as an opportunity to warn the UK Left to get real on immigration. His case for immigration controls is to make moral as well as legal distinctions about how to categorise people who come to the country seeking a better life:

“In both Italy and Germany – unlike the UK – it’s been the refugee influx, and the economic migration that has taken place alongside it, that triggered the movement towards authoritarian populism.”

Mason is either dishonest or dangerously ignorant in framing “authoritarian populism” as an isolated, brand new phenomenon that can be narrowly explained through the prism of recent migration into Europe. The suggestion again here is that the problem is numbers. There are too many “economic migrants” for communities to “integrate” or “absorb”. This mirrors exactly the arguments made by Harold Wilson and Roy Hattersley to justify the shift in position of the Labour Party over the course of the 1960s in favour of immigration controls. The reality is that this country takes in miniscule numbers of refugees compared even to other Western European states like Germany and Sweden, while 84% of the world’s refugees claim asylum in countries that neighbour their own, all of which have far fewer resources than Britain. And the number of migrants able to move to find work and a new home during times of widespread war and primitive accumulation is now murderously restricted by the new technology of border control, compared to the great nineteenth century migrations across the Atlantic undertaken by Jewish, Irish, Italian and German proletarians. At best Mason is playing politics on migration, but toying with racism as a political field is deplorable.

Corbyn’s own public comments on immigration have betrayed less of this nativist tendency though he has more than once referred to a need for any Labour government to tackle unscrupulous employers importing low-waged migrant labour to undercut existing pay and conditions. Focusing on the employer in this way still doesn’t challenge the widespread discourse that immigration is the problem. Labour’s 2017 general election manifesto speaks little about immigration though they do promise to be a “fair and reasonable” manager of it and outline a standard corporatist vision of an immigration regime brokered by government, capital and trade unions, in the interests of the “national economy”. Pledges to end indefinite immigration detention (though not detention itself) and to stop the demonisation of immigrants would obviously represent some clear improvements in conditions for migrants that cannot be dismissed, but there are hard limits to what this overall approach can offer.

The language of “fairness” merely obscures the reality of immigration control – a reality of numbers and an imperialism of violently policed borders in rich countries, preventing entry to poor people. Immigration control has represented a consensus position of both Labour and Conservative governments since the 1960s – and despite the softer words and some potentially more humane policies, this will remain the reality under a Corbyn Labour government. Indeed, Brexit is likely only to widen the pool of working class migrants targeted for arbitrary and bureaucratic hoop-jumping, punitive conditionality, and ultimately detention and deportation. As Gareth Dale outlined in a recent essay in Viewpoint Magazine:

“Far from protecting workers’ rights, immigration control divides the workforce, driving new arrivals into insecure jobs, whipping up status anxiety, vesting employers with additional techniques of control, and subjecting everyone to intensive regulation by state bureaucracies and the police. Expanding the remit of the border police and intensifying immigration surveillance would not suppress labor-market competition.”

The compositional imperatives of a party politics, a national politics, are what guide too much of today’s new “New Left”. A strategic, flattened politics of class is advanced through what is actually a broad cross-class moral populism. Immigration control is then treated as a given. Yet it is the managers of what remains of workerist institutions who are formally constrained by the borders of the nation-state, not the working class itself. And it is not a coincidence that many of the most successful contemporary struggles in workplaces in the UK are themselves led by migrants. Dale, again, addresses this question in the context of historical waves of immigration and class struggle:

“Mass immigration does not undermine the prospects of labor or the left, nor – the logical converse – does mass emigration boost them, whether in 1850s Ireland or 2000s Lithuania. The nutrients required for labor and the left to flourish are cultures of solidarity and combative agency. These emerge with changing “political opportunity structures” and social movement successes, circumstances that can obtain when immigration rates are higher, such as Western Europe in the early 1970s, or lower.”

Migration Series #40: The Migrants, Jacob Lawrence

Conclusion

The point of this essay has not been to suggest that the European working class is inherently racist. Nor have we intended to let classes and individuals with more power “off the hook”. The means to abolish racism and exploitation lies with the global working class. But as we have seen, from 1905 to the present day, based on long histories of colonialism that came before, there have been socialists determinedly looking for ways that working class people should be divided, classified and regulated. This historical longview of the British Labour movement attempts to illuminate some of these malignant threads in socialist history. It is not intended to demoralise but to remind us that the border regime as we know it is not so long in the teeth. It is just over a hundred years old and it can be undone. By contrast, calls to subvert nationalism as a left programme of sovereignty, or cynical political backing for pragmatic controls on immigration, are hopelessly flawed. It is narcissistic in the extreme to think colonial histories can be toyed with and rebranded as part of social democratic wargaming.

We felt it important to highlight the strong, consistent thread of racism throughout the history of workerist institutions like the Labour Party and the TUC, integrated into the national-political life of Britain and increasingly tolerated by the bourgeois state over time. From the 1905 Aliens Act onwards, immigration controls become increasingly normalised as a political reality, not only as a barrier to the global working class entering but as a key wellspring of racism and nativism among proletarians in Western countries. We don’t believe it is possible for these institutions to achieve an antiracist and borderless world. This is not to say that there aren’t staunch antiracists and good comrades within them, but rather that the very forms of these institutions reproduce the capital/labour relation, borders and whiteness at their core.

The American labour historian David Roediger has written of whiteness:

“To make its fullest possible contribution to the growth of a new society, activism that draws on ideas regarding the social construction of race must focus its political energies on exposing, demystifying and demeaning the particular ideology of whiteness, rather than calling into question the concept of race generally.”

“Taking shape as it does behind dams of repression, whiteness can be swept away dramatically when the dams begin to break.”

What this essay omits are the long histories of solidarity between European and non-European workers, migrant and non-migrant, between “white” and racialised; the genuine strides in antiracist organising; the steady, thankless, often ignored campaigns against deportations and detention centres that stretch back decades. The potential is there to grow these communities of solidarity further and to spread these struggles, for the dams of whiteness to begin to break. The questions of how are being addressed every day, in theory and practice, by people engaged in the struggle against racism, class and borders.

By Michael Richmond (@Sisyphusa) & Alex Charnley (@steinosteino)